Baseball’s Hall of Fame officially welcomed four new members on Wednesday with Chipper Jones, Vladimir Guerrero, Jim Thome and Trevor Hoffman being selected for the honor.

It’s a fine class and while you might read people debating the worthiness of any of those players in some places, you won’t see that here. All four of those gentlemen belong in Cooperstown.

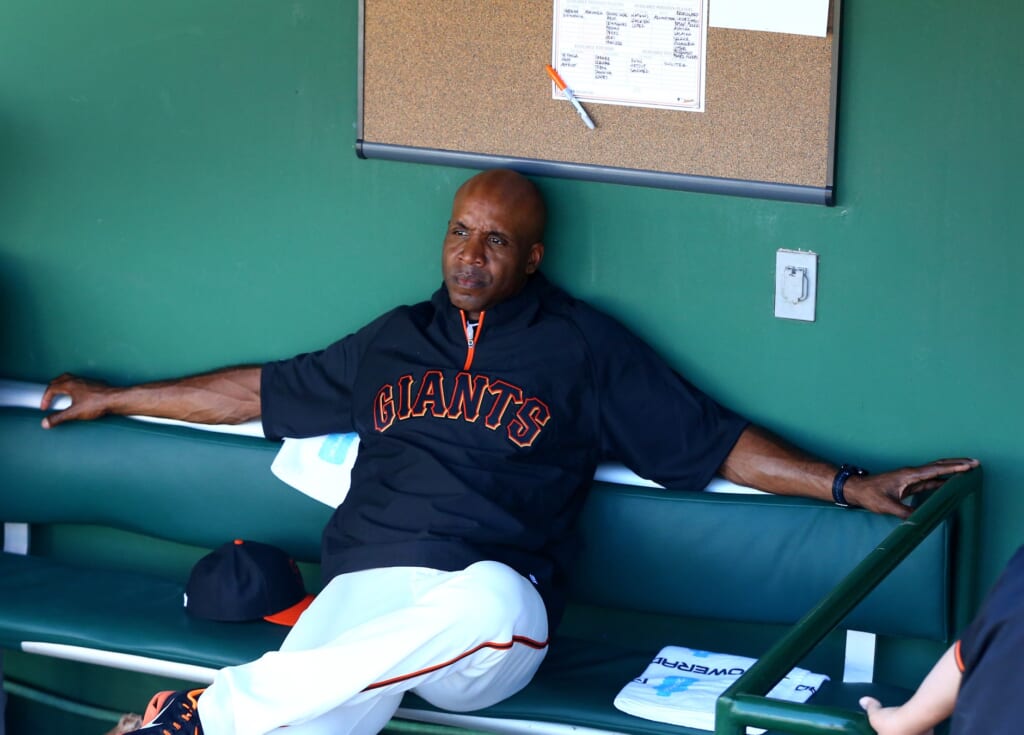

Feathers were ruffled with the exclusion of some players — notably Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens. Of all of the alleged (and proven) PED users, Bonds and Clemens are the most likely to get in. The general consensus (largely backed up by the Mitchell Report) is that both had Hall of Fame resumes before the alleged PED use began. So, even if we discount everything that was done afterwards, they belong.

But in fact, Bonds and Clemens don’t belong in the Hall of Fame because of what they did before the alleged PED use started. They — along with many others — belong in the Hall of Fame because of the alleged PED use.

It’s a strange argument, we concede. But there are two different angles to look at here.

The first angle is simple. The Baseball Hall of Fame is a museum. Museums are supposed to represent the history of their subjects, both good and bad.

For example, it’s undeniable that Guns N’ Roses was a wildly popular rock band in the late-80s and early-90s. It’s also undeniable that the egos of the members, namely Axl Rose and Slash, had the main members of that band to be at odds with each other. That caused the band to split up into completely unrecognizable factions for more than 20 years . If the day comes when a Guns N’ Roses museum is created, it can’t just feature stories behind Welcome To The Jungle, Paradise City, Sweet Child O’ Mine and November Rain. If the infighting isn’t detailed, that museum won’t tell an accurate history of its subject.

The same basic concept applies in baseball. The Steroid Era is one of the negative clouds that hangs over baseball. Baseball’s full history is not being told if members of that era are not in what should be baseball’s ultimate museum.

Which brings us to our second perspective.

An argument against these guys has long been that honoring those who allegedly take shortcuts is an insult to those who didn’t. That’s essentially what the November letter from Hall of Famer Joe Morgan — which you can read without secondhand commentary here — said.

Its not that we can’t see where Morgan is coming from. But he is looking at this from the wrong angle. Having the Steroid Era recognized actually puts the clean players, like Morgan, in a better light.

Babe Ruth was great for many reasons. His home runs were so massive and his numbers so gaudy that more than 80 years after his final MLB game and 70 years after his death, he’s still baseball’s greatest icon. But those numbers alone weren’t what made Ruth such a legend.

Ruth’s peak seasons came in the 1920s, when baseball really needed something good. The Chicago White Sox throwing the 1919 World Series had done seemingly irreparable damage to the sport. Yes, there had been rumblings about players throwing games in the past. But eight players from one team conspiring to throw away that game’s greatest prize? How could fans have any confidence in the sport after something like that?

It was tough. But all of a sudden Ruth, who had been one of baseball’s most promising young players, started to rewrite the record books. In 1920, Ruth hit 54 home runs. That nearly doubled his own record of 29 from the previous year. He broke the record again with 59 in 1921 and 60 in 1927, a record that stood until 1961. A sport that had seemingly irreparable damage done to it in 1919 all of a sudden had a star that people couldn’t look away from the following year.

So what happens if we learn about everything Ruth did, but forget about the Black Sox? All of a sudden, Ruth’s impact doesn’t look quite as immense. He put up incredible numbers. But without also knowing about that 1919 World Series, you don’t really realize that the Babe probably saved baseball. That puts his status in MLB history at a completely new level.

The same basic idea applies with the alleged and confirmed PED users.

Barry Bonds hit a record 762 home runs in his career. It’s hard to figure out exactly how many he would have hit if he had stayed clean, but we can make a pretty decent guess.

For now, let’s say that Bonds began using PEDs after the Mark McGwire/Sammy Sosa home run craze of 1998. Bonds finished the 1998 season with 411 career home runs, averaging .0216 home runs per game.

From 1999-2007, he averaged .0322 home runs a game. Extrapolating that out, Bonds averaged 35 home runs per 162 games through 1998, and 53 per 162 after.

Projecting what he would have done without the alleged PED use for the rest of his career is tricky. But let’s say that without the PEDs, he would have played through 2005, which was his age 40 season, averaging 150 games played a year. For the sake of this argument, let’s also assume that a clean Bonds would have continued to average the .0216 home runs per game.

At that rate, Bonds would have finished his career at 656 home runs. That’s absolutely a Hall of Fame total, especially when factoring in the rest of Bonds’ game. But it’s still 99 short of Hank Aaron.

Frankly, those estimates cut Bonds a lot of slack. It’s not likely that he would have played 150 games a year into his late-30s and beyond. It’s also unlikely that he would have continued to homer at the same pace. But even giving him that slack, he’s not terribly close to Aaron.

Reading that, doesn’t Aaron’s career mark of 755 home runs look better? Bonds, a great player, allegedly took the PED shortcut to help buy himself about 100 home runs, and still only hit seven more homers than what Aaron did without PEDs.

That should be pointed out in Cooperstown. If you need a section of the Hall of Fame that isolates the presumed PED users, that’s fine. For that matter, let’s throw in the 1919 White Sox and Pete Rose. Without them, the Hall of Fame lacks the perspective it needs to be a true baseball, as well.

By keeping these people out, the Hall of Fame voters aren’t just omitting a large part of the game’s history. They’re actually doing a disservice to the more positive parts of baseball’s history.