With the bigger bases and the limit on pitchers throwing to first to try to deter prospective base thieves, stolen bases and the percentage of success both are up this season in MLB.

Early stats have the success rate at nearly 83 percent this year as compared to 75 percent in 2022 and more than 150 additional bases already have been stolen, relative to last year. There could be as many as a half dozen players swipe 50 or more bags this year and that hasn’t happened since 1992 when there were five.

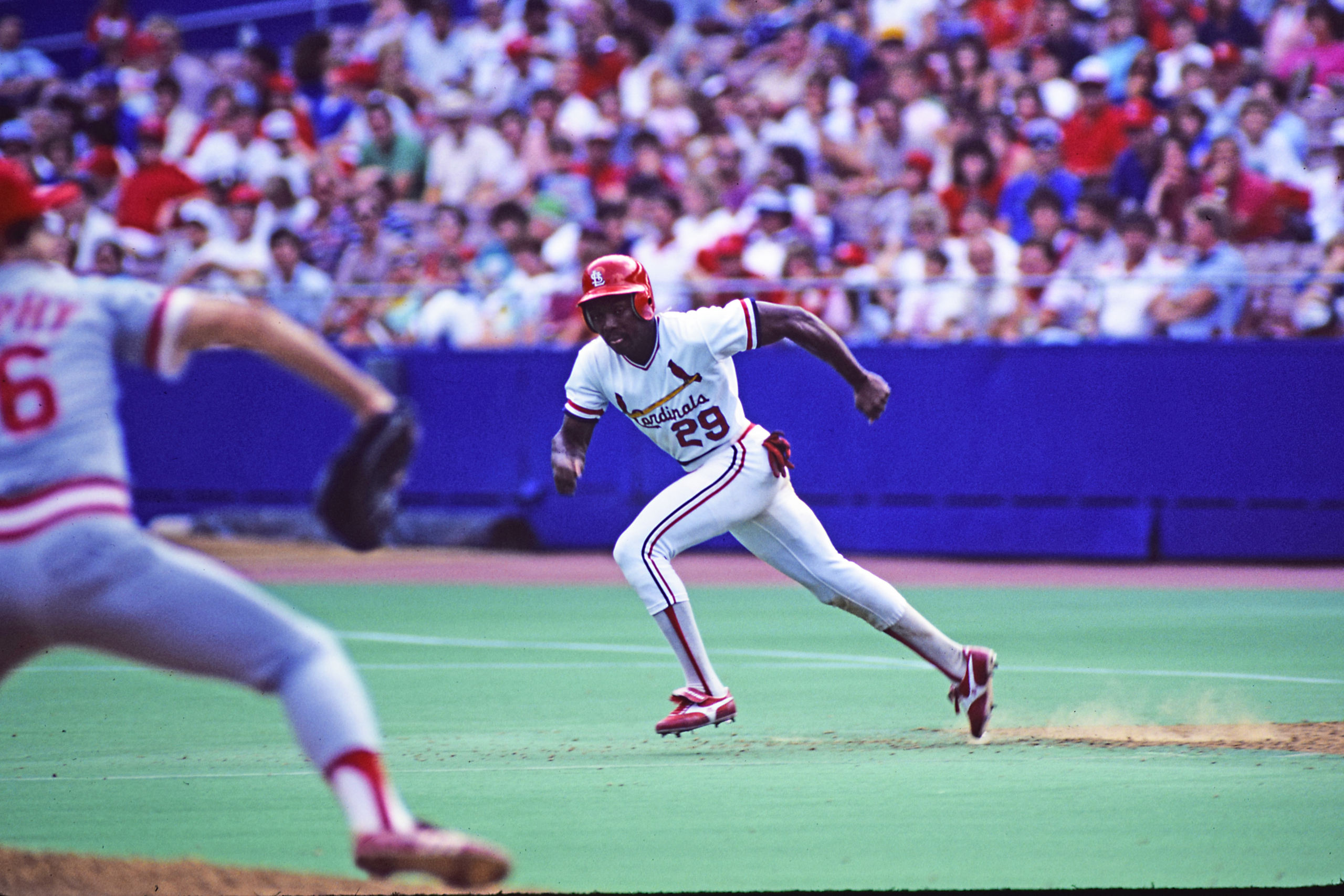

But former St. Louis Cardinals speedster Vince Coleman, who was the last player to heist 100 or more bases — he did it three consecutive years from 1985-87 — doesn’t see this is as necessarily a major trend.

“You look at our teams in the 1980s which were designed around base stealing from the leadoff position. That was our way to be impactful and the opposition would be on edge,” Coleman told Sportsnaut. “Today’s game is a little different. They’ve made the bases bigger and they’ve given guys a few more opportunities but are those guys really base stealers?

“You won’t see 100. The organizations aren’t going to allow the managers to say that’s not too much of a risk.”

How would new MLB rules impact Vince Coleman?

Stolen bases have steadily decreased since the 1980s. Even all-time MLB stolen base leader Ricky Henderson didn’t top more than 66 steals after the 1980s. In the 2000s, only three players have stolen 70 or more bases — Jose Reyes (78 in 2007), Scott Podsednik (70 in 2004), and Jacoby Ellsbury (70 in 2009).

But Coleman said he didn’t think MLB’s new rules would influence him to steal any more bases anyway.

“If I was to get on base more, if I had an on-base percentage of more than .400, then I would say yes,” he said, laughing.

“Would I steal more bases today? But stealing bases isn’t that easy. It’s still a complex situation where you have to have that mentality of ‘I want to.'”

Relative to the pitchers getting only two throws to first — or disengagements — per hitter, Coleman said that wouldn’t have affected him. “I was looking to go on the first or second pitch anyway,” he said.

“But being able to throw over only two times — what that does, it puts your defense in a position that, after the second time, you know fastballs are going to come from a pitcher. You know what? I might have had less stolen bases today because if Willie McGee and Jack Clark were hitting behind me now, as they were then, they weren’t going to be taking that fastball.”

Pick-off moves and steals

Coleman recalls former Cincinnati left-hander Chris Welch throwing more often to first base to try to detain Coleman than anybody else. “Seventeen straight times,” said Coleman. “I finally took off — and was safe. Everybody knew I was going. It didn’t matter if you threw over 10 or 15 times.

“If you knew you could only throw over two times, like now, you knew I was going that third time. Why throw over at all? Why waste the time?”

Again, though, Coleman perceives now that MLB teams aren’t paying attention to particular base stealing threats, as they did for him. “They’re just taking off now,” he said. “They’re just catching them off guard because they’re not really paying attention to you. It’s almost like a delayed steal.

“But it’s not really a big impact on your team. You would like to have more runners in scoring position but with less strikeouts.”

Baseball probably hasn’t figured out that last problem yet.

Rick Hummel, who was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame for baseball writing, is the baseball columnist for Sportsnaut.