“Baseball was rooted not just in the past but in the culture of the country; it was celebrated in the nation’s literature and songs. When a poor American boy dreamed of escaping his grim life, his fantasy probably involved becoming a professional baseball player. It was not so much the national sport as the binding national myth.” –David Halberstam, Summer of ‘49

The room is gray in my memory. On the top floor of my grandparents’ house, a straight shot from the end of the staircase, it sits vacant for most of the day—an empty shrine to memory. Walk in and you’ll find yourself surrounded by the past.

Look to the right and see a small table, with two baseballs sitting on top of it. The first is clean and holds a lone signature, identifiable at a distance: Pee Wee Reese: 10-time All-Star, Hall of Famer, and 1955 World Champion.

The second requires a closer look. There’s a veneer of dirt on it, as if, years ago, someone made contact with it, producing a swinging bunt that rolled along the foul line. Originally, in pencil, the signatures are faded, but an astute observer will recognize some of them on sight: Robinson, Campanella, Hodges, Snider, and Reese again, along with about 20 others.

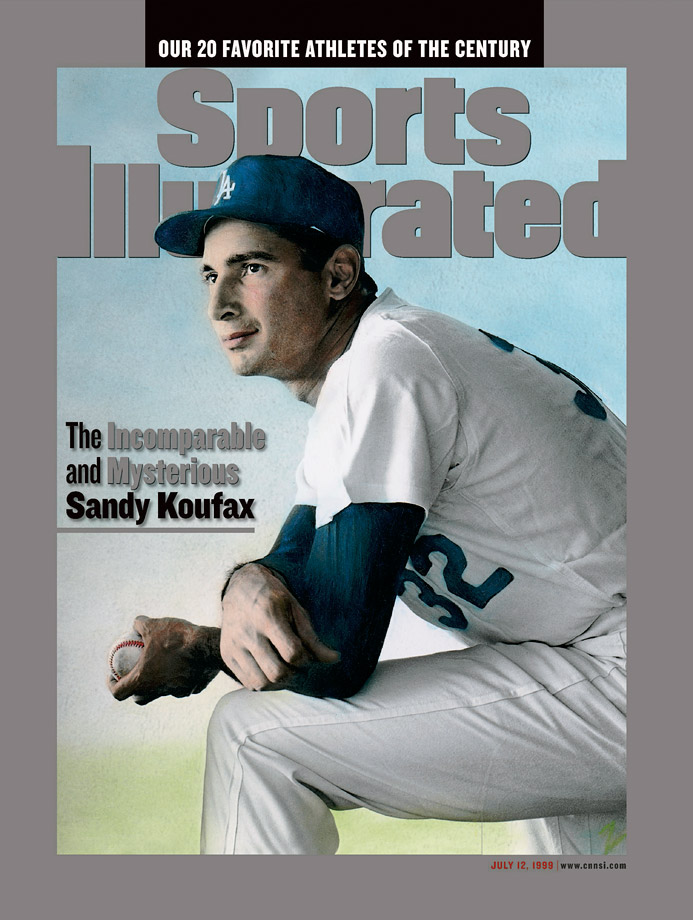

Put the ball down and step back, looking around again. There’s an old Sports Illustrated—not quite as old as the balls, but from the last century: July 12, 1999 to be exact.

On it, a young Sandy Koufax sits with no glove but a baseball in the legendary left hand that produced the greatest five-year run in history before imploding on its owner. “OUR 20 FAVORITE ATHLETES OF THE CENTURY”, reads the banner up top, with “The Incomparable and Mysterious Sandy Koufax,” a bit lower down.

Thumb through the issue and find a recap of a Sampras-Agassi Wimbledon final, a profile of a young Tiger Woods fresh off a win at Western, a tribute to Tiger Stadium in its last season. Then, finally, the headline you’re looking for: “The Left Arm of God.” Read the story, enthralled at the sheer mythology of Koufax, who won Game 7 of the 1965 World Series on two days rest throwing only fastballs, then look up and notice the framed portrait on the back wall.

Surprisingly in color, the faces are as easily recognizable as the names on the ball—in fact, many of them are the exact same. The 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers sit in living color, Ebbets Field the backdrop. On the bottom right sits Roy Campanella, arms crossed—along with the rest of the row—with the face of a man who had lost in the World Series for three of the last six seasons—practically withered compared to the 25 year old, beaming Sandy Amoros sitting to his right.

Two rows above Campanella is Jackie Robinson. Look closely and you can see the chair he’s standing on. Robinson and his counterparts in the third have their arms crossed behind their backs, as do the players in the second row. Next to that portrait: you notice the Daily News front page from October 4, 1955. “WHO’S A BUM,” screams the headline, accompanied by a drawing of a man, wide-eyed, mouth open, hair unkempt.

Some background: my grandfather was born in 1940—right before the winds of change swept baseball and soon after the country. He grew up in Flatbush, just blocks from Ebbets Field and the Brooklyn Dodgers. As a kid, he could walk a few blocks to Ebbets Field on a sticky summer day and sneak his way into the concourse to watch the team. And what a team it was. Between the time he was born and the Dodgers packing up and moving to Los Angeles, the team won seven pennants, yet became the national symbol of heartbreak.

Whether it was Mickey Owen dropping the third strike, Bobby Thompson hitting a walk-off home run or Billy Martin making an impossible catch, the Dodgers found a way to lose. Until 1955 that is, when the tables turned. Robinson stole home, Podres pitched a shutout. And suddenly, the lovable losers were losers no more.

A short time later, owner Walter O’Malley packed up and moved the team out west, breaking the hearts of the Brooklyn faithful. The Mets arrived to fill the void in 1962—my grandfather now roots for them—but nobody in their right mind will tell you it’s the same.

Those Dodgers, in so many ways, encompassed the mythology of baseball. Brooklyn wasn’t just a group of lovable losers that eventually overcame years of heartbreak, it was the breeding ground for the social change that would envelop the country for over 20 years after Jackie Robinson set foot onto the grounds at Ebbets Field.

It featured more mythological players with names out of fairy tales—Duke, Dixie, Preacher, Pee-Wee, Sandy (though not all at the same time)—than just about any other team of that era. Even its broadcasters, Red Barber and Vin Scully, instantly transported you to the beautiful blue-skies and green grass of a perfect summer day.

In America, baseball has always represented something more than the game itself. Halberstam called it the binding national myth, but it’s more than that. Baseball is the innocence of believing the lovable losers can win. Baseball is the belief that you can become one of your heroes. Baseball is summer—when the children are out of school and running rampant on the town. Baseball is stepping out onto the field in the morning, seeing the dew on the grass, smiling and saying, “Let’s play two.”

Baseball is the picture-perfect vision of American idealism: a uniting game during the Civil War, played by soldiers on both sides as their families were torn apart, expanding westward as the sporting version of Manifest Destiny, harnessing the power of radio to reach the ears of millions and later on, reaching the eyes of millions more through television.

America mythologizes baseball players, because, throughout the game’s history, they’ve been built up as the model Americans. When corruption plagued the game, Kenesaw Mountain Landis came in and ended it. When Bob Feller was driving his Buick Century across the Mississippi in December 1941 and heard on the radio that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor, he dropped everything and enlisted in the Navy, as did most other players of the time.

When players across the league and even on his own team hurled abuse at Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese stood by his side and put an arm around him, welcoming a new era of integration and the hope for equality. When Curt Flood failed to end the reserve clause Marvin Miller kept up the fight and won rights for the union.

“Baseball has marked the time,” Terence Mann said, “It reminds us of all that once was good and it could be again.”

However, that feeling has eroded in recent years. Of the five lowest-rated World Series since 1984, four have been in this decade. Young people tend to think the game is too slow. And while MLB has tried to speed things up, perception hasn’t changed. And in 2016, the last two pillars of baseball history crashed down 32 days apart.

On October 2, 2016, Vin Scully stepped down from the microphone for good. Baseball’s own Mr. Rogers had a poetic ending to his career—the Dodgers clinched the NL West in his last home game and the video aired after his final game noted that it was eighty years to the day since Scully started to love baseball.

But his retirement marked the end of a long line of baseball broadcasters that came to define their cities. There is no Mel Allen, Red Barber, Jack Buck or Ernie Harwell remaining to spin stories or put kids to sleep. And perhaps, there’s no room for one to emerge. Scully was the last of that breed—can you imagine another broadcaster compelling a crowd to wish the umpire a happy birthday?

Thirty-two days after Scully left the game, the Chicago Cubs broke a 108-year losing streak. There was no black cat, Bartman, or any other one of baseball’s one-word calamities awaiting them in Cleveland. Only a ground ball, fielded cleanly, to end a century of defeat. But something else ended with that ground ball. When Kris Bryant’s throw sailed across the infield grass into the glove of Anthony Rizzo, baseball’s journey to becoming Just Another Sport came to an end.

There is no more mythology—at least none of it living. There is no more symbolic trek toward the American Dream, no more transistor radios to put under the pillow. When the season opens up again on Sunday, we’ll say hello to summer again, but with the internal knowledge that baseball is nothing but a game.